Focused Meditation Changes Clustering of Brain Systems

By John M. de Castro, Ph.D.

“meditation . . . appears to have an amazing variety of neurological benefits – from changes in grey matter volume to reduced activity in the “me” centers of the brain to enhanced connectivity between brain regions.” – Alice G. Walton

The nervous system is a dynamic entity, constantly changing and adapting to the environment. It will change size, activity, and connectivity in response to experience. These changes in the brain are called neuroplasticity. Over the last decade neuroscience has been studying the effects of contemplative practices on the brain and has identified neuroplastic changes in widespread area. and have found that meditation practice appears to mold and change the brain, producing psychological, physical, and spiritual benefits. These brain changes with mindfulness practice are important and need to be further investigates.

Meditation practice results in a shift in mental processing. It produces a reduction of mind wandering and self-referential thinking and an increase in attention and higher-level thinking. The neural system that underlie mind wandering is termed the Default Mode Network (DMN) and consists in a set of brain structures including medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, lateral temporal cortex and the hippocampus. The neural system that underlies executive functions such as attention and higher-level thinking is termed the Fronto-Parietal Network (FPN). and includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and cingulate cortex.

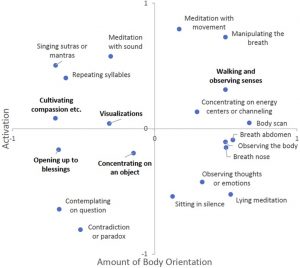

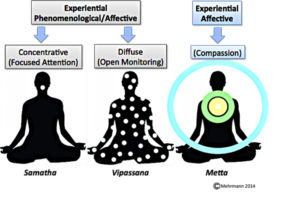

There are a number of different types of meditation. Classically they’ve been characterized on a continuum with the degree and type of attentional focus. In focused attention meditation, the individual practices paying attention to a single meditation object. In today’s Research News article “Revealing Changes in Brain Functional Networks Caused by Focused-Attention Meditation Using Tucker3 Clustering.” (See summary below or view the full text of the study at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6990115/), Miyoshi and colleagues examine the changes in the brain’s functional systems resulting from meditation practice. They recruited meditation naïve adults. They had their brains scanned with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) during a 5-minute rest and a 5-minute breath-following (Focused) meditation.

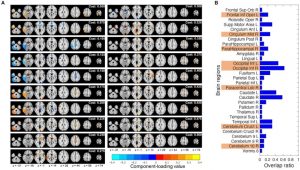

They found in comparison to rest, during the brief focused meditation there was increased clustering in “eight brain regions, Frontal Inferior Operculum L, Occipital Inferior R, ParaHippocampal R, Cerebellum 10 R, Cingulum Middle R, Cerebellum Crus1 L, Occipital Inferior L, and Paracentral Lobule R increased through the meditation.” These are all regions involved in the Default Mode Network (DMN), the Somatosensory Network (SSN), and the Fronto-Parietal Network (FPN). The activity of these clusters best discriminated between the resting and focused meditative states.

These results make sense in that during a typical meditation there will be attentional focus, mind wandering, and return to attentional focus. The attentional focus is thought to involve the Fronto-Parietal Network (FPN). The mind wandering is thought to involve the Default Mode Network (DMN). Finally, returning from mind wandering to attentional focus is thought to involve Somatosensory Network (SSN). Hence the increased clustering in these systems seen in the focused meditative state would be expected given what is known of neural systems.

These results are from a very brief single focused meditation by meditation naïve participants. So, it does not reflect neuroplastic changes in the nervous system that would be expected in practiced meditators. Rather the results indicate the short term activation of clustered systems in the brain that if practiced over time would produce neuroplastic changes.

So, focused meditation changes clustering of brain systems.

“long-term, active meditative practice decreases activity in the default network. This is the brain network associated with the brain at rest — just letting your mind wander with no particular goal in mind — and includes brain areas like the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex.” – Kayt Sukel

CMCS – Center for Mindfulness and Contemplative Studies

This and other Contemplative Studies posts are also available on Google+ https://plus.google.com/106784388191201299496/posts and on Twitter @MindfulResearch

Study Summary

Miyoshi, T., Tanioka, K., Yamamoto, S., Yadohisa, H., Hiroyasu, T., & Hiwa, S. (2020). Revealing Changes in Brain Functional Networks Caused by Focused-Attention Meditation Using Tucker3 Clustering. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 13, 473. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00473

Abstract

This study examines the effects of focused-attention meditation on functional brain states in novice meditators. There are a number of feature metrics for functional brain states, such as functional connectivity, graph theoretical metrics, and amplitude of low frequency fluctuation (ALFF). It is necessary to choose appropriate metrics and also to specify the region of interests (ROIs) from a number of brain regions. Here, we use a Tucker3 clustering method, which simultaneously selects the feature vectors (graph theoretical metrics and fractional ALFF) and the ROIs that can discriminate between resting and meditative states based on the characteristics of the given data. In this study, breath-counting meditation, one of the most popular forms of focused-attention meditation, was used and brain activities during resting and meditation states were measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging. The results indicated that the clustering coefficients of the eight brain regions, Frontal Inferior Operculum L, Occipital Inferior R, ParaHippocampal R, Cerebellum 10 R, Cingulum Middle R, Cerebellum Crus1 L, Occipital Inferior L, and Paracentral Lobule R increased through the meditation. Our study also provided the framework of data-driven brain functional analysis and confirmed its effectiveness on analyzing neural basis of focused-attention meditation.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6990115/