Improve College Students’ Well-Being with Balanced Time Perspective and Mindfulness

By John M. de Castro, Ph.D.

“a higher level of mindfulness promotes a more balanced time perspective, with a reduced focus on negative aspects of the past and negative anticipations of the future.” – Michael Rönnlund

Mindfulness stresses present moment awareness, minimizing focus on past memories and

future planning. But, to effectively navigate the environment it is necessary to remember past experiences and project future consequences of behavior. So, there is a need to be balanced such that the amount of attention focused on the past, present, and future is balanced. This has been termed as balance time perspective. Mindfulness helps improve balanced time perspective and improve well-being. The relationship of mindfulness and balanced time perspective with psychological well-being needs further investigation.

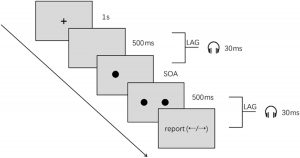

In today’s Research News article “Mindfulness and Balanced Time Perspective: Predictive Model of Psychological Well-Being and Gender Differences in College Students.” (See summary below or view the full text of the study at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8946884/ ) Fuentes and colleagues recruited university students and had them complete measures of mindfulness, psychological well-being, and time perspective, including measures of past positive, past negative, present hedonistic, present fatalistic, and future.

They found that the higher the levels of mindfulness, the higher the levels of psychological well-being future, balanced time perspective and past positive time perspectives, and the lower the levels of balanced time perspective, past negative, and present fatalistic. In addition, the higher the levels of psychological well-being the higher the levels of balanced time perspective, future, and past positive time perspectives, and the lower the levels of past negative and present fatalistic. They also found that women had higher levels of past positive time perspective while men had higher levels of present hedonistic time perspective.

“It appears that, together, mindfulness and [balanced time perspective] promote optimal psychological functioning beyond alleviating or reducing discomfort.” – Authors conclusion. In other word when mindfulness is high and the amount of attention focused on the past, present, and future is balanced there are greater levels of psychological well-being. It remains to be seen if training in balanced time perspective will result in greater psychological health.

“Both mindfulness and Balanced Time Perspective (BTP) are well confirmed and robust predictors of various aspects of well-being.” – Maciej Stolarsk

CMCS – Center for Mindfulness and Contemplative Studies

This and other Contemplative Studies posts are also available on Twitter @MindfulResearch

Study Summary

Fuentes, A., Oyanadel, C., Zimbardo, P., González-Loyola, M., Olivera-Figueroa, L. A., & Peñate, W. (2022). Mindfulness and Balanced Time Perspective: Predictive Model of Psychological Well-Being and Gender Differences in College Students. European journal of investigation in health, psychology and education, 12(3), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12030022

Abstract

Background: The aims of the study were to establish an adjustment model to analyze the relationship among mindfulness, balanced time perspective (BTP) and psychological well-being (PWB) in college students and to explore gender differences among the variables. Method: The sample consisted of 380 college students, 220 women and 160 men, uniformly distributed according to the university’s faculties. Results: The results indicate that the synergy between mindfulness and BTP predicts the variance of PWB by 55%. Regarding gender differences, it was found that women have a greater tendency towards Past Positive than men and men a higher tendency towards Present Hedonistic than women. In addition, in the group of women, a stronger relationship was found among the variables and, consequently, a greater predictive value for PWB (58%), displaying an enhanced disposition to high PWB compared to men. Conclusions: Together, mindfulness and BTP promote optimal psychological functioning and alleviate or reduce discomfort. Thus, their promotion and training in universities is especially important given the high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in college students.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8946884/